A temple to Athena

30th Aug 2018

by Miranda Sawyer

Do you collect art? Of course you do. Not the bank-busting originals, the investment pieces bartered by hedge-fund analysts and arms dealers, secured by museums for the enlightenment of the nation. I mean the pictures you put on your wall to fill the space above the mantelpiece, to tone in with the sofa, to cover the stain and your first three attempts at drilling a hole to hang the thing up in the first place. Your art: the pictures and posters and objects that mean something to you, demonstrate your allegiances, history, hopes and taste, whether Sarah Beeny-approved or not.

It sticks to you, that kind of art, as you make your way through life. It makes you laugh, or it was a gift, or it reminds you of a particular time. Maybe you were collecting that sort of stuff for a while. Sometimes you might not even like it at all: in our flat, we have a water-colour of a gated field and trees, not particularly to anyone's taste. But my granny painted it, so up it went. And after living with it for a few years, I've grown to like its splodgy greens and browns, its smudged suburban calm.

What else do we have in our home art collection? Oh, you know: framed adverts for long-gone nightclubs, Soviet propaganda pictures, old Olympic posters, school diagrams, a couple of artists' limited-edition prints. Loads of family photos and silly second-hand knick-knacks: a board with numbers for scoring pool, a teapot that looks like a cat, Padre Pio as a snow-shaker, a Michelin man advertising board. Junk, really, but we like it. It's our art, the stuff we look at day to day. Some of it cheap, some more expensive (usually it's the framing that costs), most of it found in charity shops, on eBay, in markets. None of it valuable. It wouldn't justify a special listing on your home insurance policy.

But the art you want in your house is not the same as what you wish to see in a gallery. I love Mother and Child Divided, Damien Hirst's glass-enclosed halves of a cow and her calf, but I'm not sure where I'd put them in our place. Behind the sofa? You'd have to make your home in a warehouse in order to house them, with all the chilly discomfort that that would entail… I once went to an artist's party hosted by a patron in her gorgeous town-house in west London. When I walked in, I thought I was in a restaurant. It was the paintings on the wall: so impressive and gallery-esque, I'd automatically dismissed the idea that anyone could exist happily alongside them in real, everyday life.

This difference, between "proper" art and your own beloved tat, was made explicit by Alan Kane at Frieze this year. In Frame, the new galleries section, he showed his mother's art collection. He took the stuff his mum had in her lounge and displayed it all in correct gallery manner. Separate plinths were given to a funny clay sheep, a Virgin Airways commemorative thimble, a collection of three china Japanese ladies. On the walls leant a chaffinch embroidered on to Binka, a framed picture of his mum and dad meeting the Pope and one of those photo-collages made up from cut-out snaps of the kids and grandkids. The presentation gave each piece a new status, made you look at them in a new, starry light.

Kane is a regular collaborator with Jeremy Deller, and together they run the Folk Archive, which collects and collates art ignored by the contemporary art world: embroidered wrestler costumes, hand-crafted protest banners, photographs of sound systems, or revellers on Bonfire Night. It's art that comes from ordinary people's passions: the archive forms and honours a history of everyday life. If an alien from the future were to get their sucker pads on it, they'd find such folk art far more revealing of who we are and how we live than any feted contemporary artist with their oblique references and conceptual thinking.

Similarly, the art you have in your home tells a visitor much more than you may want it to. When I first met my husband, he had on his shelves four of the exact same black-and-white postcards that I had on mine: a young George Best, a youngish Richard Burton, a →← smoke-drenched Lee Perry and Phil Daniels as Jimmy in Quadrophenia. Perhaps it showed that we were meant to be together. (We both like coffee, too: amazing!) Or perhaps it shows that we both grew up in a time of fewer cultural references, a smaller range of postcards.

Images from music, film and football aren't quite art, though. They're part of popular culture, something that is foisted on you from outside. You're a fan, so you show that by getting a postcard of your hero. But there is another type of popular art, that sells in its millions, that isn't imposed upon the public by corporations or taste-makers, but chosen by ordinary consumers of their own free will. Stuff like the pictures illustrating this piece. No one quite understands why these images are so loved, what made us buy them in their millions to decorate our homes across the world. These are not works of critical acclaim – quite the opposite – yet they're as well-known as the Mona Lisa, as home-friendly as a kettle. As popular as toast.

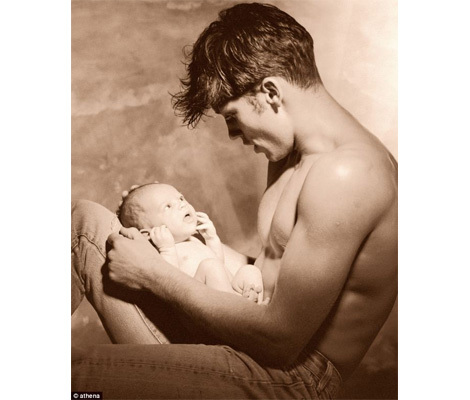

Art On Your Wall, part of the Modern Beauty Season, on BBC2, which starts on 14 November, examines seven of these pieces of mass-market art. Four are very familiar: the Green Lady, Tennis Girl, Man and Baby, Jack Vettriano's Singing Butler. Less well-known, though still amazingly popular, are Ullswater, (a photograph of a jetty extending into a lake, available at Ikea), Doris Earwigging (like a greetings card: two fat-bottomed ladies and a fat-bottomed dog) and the truly astonishing Wings of Love, quite possibly my favourite. What a picture! Hunky fella, gorgeous girl, both turned away so you don't see their naughty bits, and also so they can simultaneously contemplate the unfathomable sea, universal metaphor for life and death, lapping across what appears to be the floor tiles of the world's most enormous public convenience. There's a vast, Dalí-esque, dream-like space around the couple, but they themselves are encircled by the wings of an enormous swan. The swan is gently depositing the man to earth for his lady-love. The swan's tender trap, as well as the realistic detail, transports the picture from mere poster into the heady realms of late 70s double album cover. Swoonalicious.

Wayne Hemingway, designer and connoisseur of mass-market art, owns Wings of Love. He genuinely loves the picture: "Who wouldn't want the love of their life to arrive on the wings of a swan?" He tells me that it was in Mike Leigh's Abigail's Party and, he insists, there was a version in Saddam Hussein's palace: "In those photos of American soldiers sitting in his pool, you can see a massive mural of it behind them." Apparently, the picture is particularly popular among Middle Eastern and Russian people; anyhow, it's one of the biggest-selling prints in the world. Even in 2000, 28 years after it was first painted, it was still selling at a rate of 200 a day.

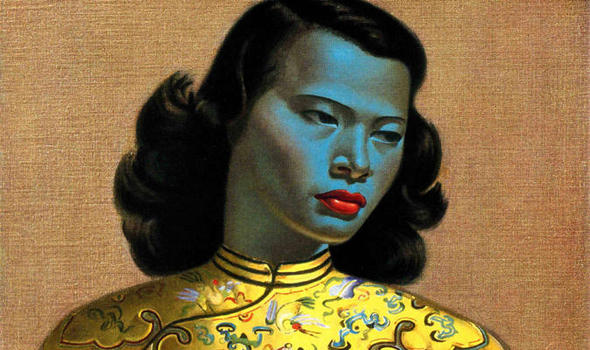

Despite this, I can't say I remember it decorating many of the homes of my youth – unlike the trailblazer of popular art, the iconic Green Lady, aka Chinese Girl. She was everywhere when I was young. She was a real person (though not green) called Lenka, a girl spotted by the Russian painter Vladimir Tretchikoff in a New York restaurant in the late 1940s: they ended up having a long-term affair. Tretchikoff was the world's first mass-market artist, deciding to mass-produce his prints in 1952, when he was 39. Though he lost his cachet among rich collectors almost instantaneously, his print sales made him the most highly paid artist in the world after Picasso. Even now, the Green Lady remains one of the three bestselling prints ever.

Lenka's portrait has long been reclaimed by the cool, with its burnished 70s colours, its spooky atmosphere and acceptably kitsch air. But back in 1970s UK, it represented something else: the tingle of the exotic. Those who displayed a Green Lady showed sophistication: in an era before package holidays, when your summer holiday was in Rhyl or Skegness, a Green Lady was shorthand for well travelled, racy, open-minded.

The Green Lady, in fact, was the epitome of romance; and romance is the signature quality of all these mass-market works. A snatched kiss outside a French café, a dinner dance on a windy beach, a tender yet masculine male model able to hold your baby without dropping it on its head: all adorably romantic ideas brought to life by these pictures. Call it sentimentality, call it hope – either way, it's notable that most of mass-market art is bought by women. Even the Tennis Girl, a bachelor's poster if ever there was one, was, according to its creator Martin Elliott, mostly a feminine purchase. "We put it down to two things. One: by buying it, it showed that the lady was a good sort. Two: it kept their men's minds off the dirtier stuff."

Back in the 70s and early 80s, prints were sold like 7in singles – on the high street, a new →← one issued every week. You could pick one up at Woolies or Boots on your Saturday shop. Many were sold via catalogues like Freemans, which accounts for the Green Lady and Wings of Love having a working-class/aspiring middle-class clientele. As did all those funny pictures of scruffy, big-eyed street urchins, often crying, or with a small dog pulling down their pants. I'm not quite sure what the romance was in those. Perhaps they just reminded their owners of a time when their kids were cute. Or perhaps it was in the idea that you could rescue these poor mites, who were often from foreign climes, or past times: dressed in Spanish flamenco outfits, or Dickensian rags. Like the Green Lady, they showed that you knew about places other than your local town.

They also had a cheeky quality, which much of popular art has, in Britain at least. I speak to Katy Elliott, commissioning editor of the Art Group, which operates under an Art for All philosophy. The Art Group has been going for 22 years and offers greetings cards and "wall art", supplying much of today's high-street shops with their artistic offerings, from John Lewis to Argos to Tesco. If you've bought a framed print in Ikea or a canvas from Habitat, the likelihood is that it came from The Art Group.

Katy tells me that the British are less prudish than both the Americans and the Scandinavians. Which fits in with the silly, saucy element of our preferred mass-market art, the flip to our romantic side, seen in Sam Toft's chubby-bummed ladies, or Arthur Sarnoff's pink-potting hounds. Martin Elliott regards his Tennis Girl as his "photographic interpretation of the saucy seaside postcard", which seems about right.

Anyhow, Katy is up on current trends in popular art. "There's a lot of positive slogans doing well at the moment," she says. "That kind of 'make-do-and-mend' idea, spin-offs of the Keep Calm and Carry On poster. Also, nature is massive, including natural materials. Especially wood. We sell so much artwork with wood in it."

All very sensible: a far cry from the daft romance of Wings of Love or Man and Baby. Actually, when you look at what the Art Group sells, what's surprising is how middle class it all is. Cool Manhattan skylines, Hockney-style LA, black-and-white photographs, old Guinness ads, tasteful abstracts with 50s textile print references. Very nice.

But not, sadly, as extravagant, as polarising, as outrageous as some of the mass-market art of the past. Now we're all encouraged to see where we live as an investment, rather than a home, it seems that some of the fun has gone out of our popular art. We choose our pictures to blend into the tasteful whole, as just another part of the neutral, careful décor that will impress neighbours as much as prospective buyers. We don't want to be exotic, romantic, silly any more; just cool and discerning. What a shame.★

The Art on Your Wall is part of the Modern Beauty Season. It will be shown on BBC2, on 16 November, 9pm

For the full article as it appeared on The Guadian click HERE